The following article is Part II of a two-part series on the history & future of tennis in America. Catch Part I here.

Welcome to the Dance

Here is where dance is revisited - that performance of the body in movement, as an expression of our deepest selves and of the human themes that surround our everyday lives. At its core, the separation of athletics and artistry is only divided by what means to an end the body conveys. But it is also through the body we find a medium through which storytelling is conveyed across disciplines. As Venus and Serena Williams showed us with their arrival to the front stage of tennis in the late 90s and early 00's, bodies in movement have the power to transverse cultural narratives without saying a word, and lead to groundbreaking stories that pave a new way to experience sports, helping to increase interest and create revenue for the sport's continued growth.

The world of dance has experienced a similar story to the world of tennis. Like tennis, many traditional dance practices, such as ballet, were wrapped in similar behavioral codes of conduct and expectations that prohibited the sport from successfully becoming adopted around the world. However, through the push for reinvention within different dance disciplines and the cultivation for altogether new styles of dance, the art form has kept not only kept itself alive through storytelling, but is thriving as an industry.

Ballet is embedded in a long history of lavish entertainment for Europe's nobility, inclusive of all the mores that go with it. Ironically, the first push for reinvention within the practice was in fact, a philosophical and creative protest against the then popular artifice of opera-ballet. Jean Georges Noverre believed that ballet should contain expressive, dramatic movement that should reveal the relationships between characters. His work, a precursor to the ballets of the 19th century, introduced the dramatic style of narrative ballet we think of when we see the Nutcracker, Swan Lake, and Giselle. As ballet began to spread away from Europe and into countries like the United States and China, new dance styles were created to meet the tastes of the people in these countries. Yet both choreographers and dancers alike found themselves in a cultural struggle between the old world and new, trying to gain acceptance, while simultaneously satisfying the unique tastes of these newly exposed cultures. Ballet persisted and found ways to respond to cultural shifts, specifically within its style of storytelling through movement, as well as by keeping their doors open to help popularize ballet in mainstream media. These steps helped them reach new audiences outside of their fading (and aging) following. The dance style continues to prosper today.

While some dancers and dance styles reinvented themselves within the system, others found new approaches altogether. The now famous Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater started as a group of dancers from multi-racial backgrounds who came together in the late 50s. They traveled the country with their entirely new and modern approach: dancing an untold story never seen by American audiences. Ailey's most famous piece, Revelations came from Ailey's own "'blood memories' of his childhood in rural Texas and the Baptist Church." The movement and expressions of Alvin Ailey's ground breaking dance company deviated the expected protocol of traditional dance but expressed stories that mattered to a wide range of people. This approach not only worked, it helped propel Alvin Ailey to became one of the most renowned modern dance theaters in the world today.

Perhaps one of the most currently accessible and successful forms of dance - hip-hop - started around the same time as the rise of the music genre in the South Bronx, New York during the 1970s. Both hip-hop music and it's movements have gone hand-in-hand over the decades, as popular dances have moved the music forward while in turn, popular singers have moved hip-hop dance forward. Without the typical to barriers to entry such as professional training, fees, pedigree, etc., an entirely new approach to dance emerged. Hip-hop moves and movement included things the traditional world of dance had never seen before, such as breaking, popping, locking, gliding, ticking, vibrating and krumping. Within decades, hip-hop took over the world, turning both the music and dance it the billion-dollar industry.

The constant reinvention of dance throughout the centuries - whether it has been within one discipline, through the creation of another, or by mixing insights from various genres - has been imperative in keeping interest in dance not only alive, but in boosting the overall revenue needed for future growth.

"It's also a reminder that history changes as you write it." says Zoe Anderson in The Balley Lover's Companion. "So far, ballet's 21st century hasn't been revolutionary. It's been a pattern of recovery and rediscovery, of absorbing change and developing from it. The urge to wring our hands over the art form's survival has faded. Ballet's got its confidence back."

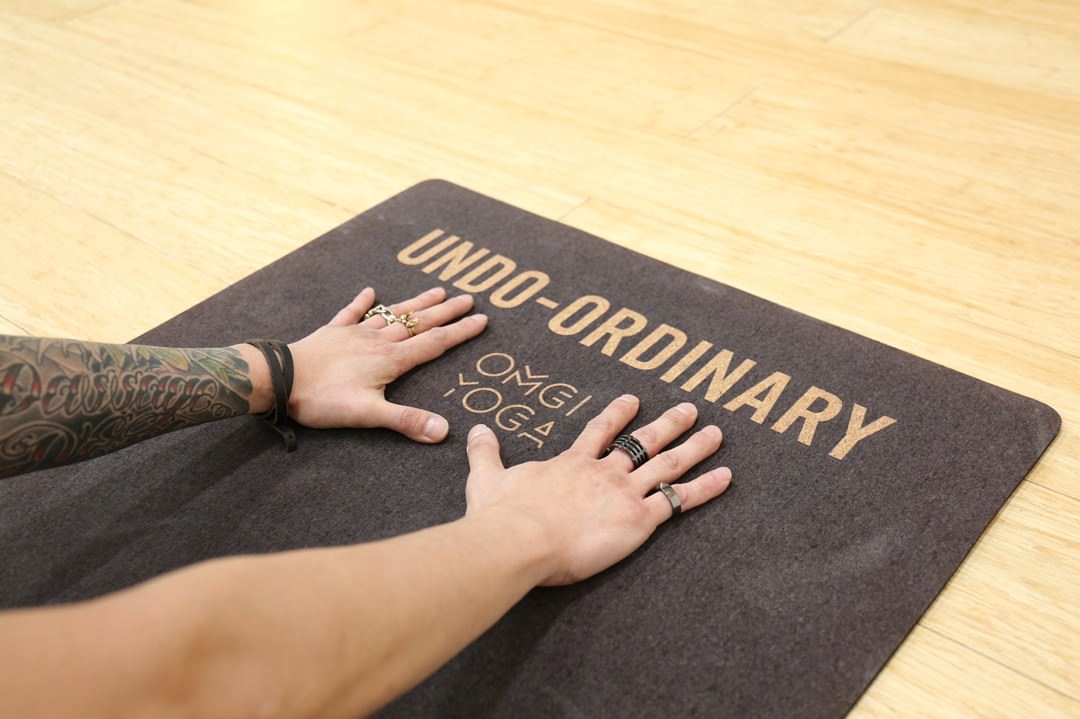

For the future of American tennis, the sport needs to take a cue from the world of dance. Like ballet, perhaps tennis should rediscover itself by absorbing change and developing into a new version of its old self. Although the industry of tennis may never build itself up to the popularity of hip-hop, there are certainly enough overlaps between the two disciplines to build out popular themes for audiences to relate to.

"So often in dance we are trying to embody movements that invite the audience to have a visceral response. Where you feel what it would be like to do that movement. We watch sports the same way. We hold our breath when someone jumps and reaches for the ball. While they are flying through the air we hold ourselves suspended in anticipation." says Edward Rice, a New York City site specific dancer who resonates strongly with the athletes on the court.

"Most of the movement I make (in dance) involves me falling, reaching, suspending, and falling again. There is an initial impulse and then seconds at a time of living through the fall out of that action….For me, some of the best dancing is in the recovery."The case of the game pictured here (Monfils vs. Jan Satral) tells the tale of an underdog with statistically little chance of beating the No. 10 ranked Monfils. Yet in Satral's posture we see the scrappiness of a hustler - nothing to lose, and everything to gain - but just a fall away from loss or the ultimate glory.

"Most of the movement I make (in dance) involves me falling, reaching, suspending, and falling again. There is an initial impulse and then seconds at a time of living through the fall out of that action….For me, some of the best dancing is in the recovery."The case of the game pictured here (Monfils vs. Jan Satral) tells the tale of an underdog with statistically little chance of beating the No. 10 ranked Monfils. Yet in Satral's posture we see the scrappiness of a hustler - nothing to lose, and everything to gain - but just a fall away from loss or the ultimate glory.

In tennis too, perhaps the most amazing elements of athleticism and performance are not in the actual result of a point, but in the flight and fall of the player. It's in the approach and recovery that stability, strength, power, and the true story, rest.

Perhaps this is where the real story of tennis emerges - in the act of reacting- without etiquette or pedigree or reserve - to the vulnerabilities that the game throws each player's way. It's in the subversive, unorthodox moments of unstructured play that tennis supersedes the reserved culture of its past, and instead, expands beyond its expected decorum to reveal all the elements of the human experience: faith, fear, greed, hate, loss, courage, pride, revenge, heroism and yes, even love.

"This image has an Ailey -esque quality to it," says Samantha Wright, a former state level tennis player in South Africa and a dancer with over 19 years of experience. She is referring to Canadian tennis player Milos Raonic serving against Germany's Dustin Brown last week in Flushing.

"This image has an Ailey -esque quality to it," says Samantha Wright, a former state level tennis player in South Africa and a dancer with over 19 years of experience. She is referring to Canadian tennis player Milos Raonic serving against Germany's Dustin Brown last week in Flushing.

"It reminds me of some of the (Ailey) works that showcase their raw power and athleticism. With some minor tweaks this could easily be a transitional movement for a contemporary dancer."

Ironically, it's Raonic's power that not only led him to the Wimbledon final this year, but helped him gain his start in tennis long ago. As an eight-year-old, Raonic went up to one of the sport's best coaches in Canada and told him he wanted to train with him. Although Raonic had no tennis experience, the coach observed his raw power on the court and eventually took him under his wing. You could say Raonic's reign, and the story helped save Canadian tennis culture, which shares a similar

You could say Raonic's reign - and his story of power - is helping to save Canadian tennis culture, which shares a similar struggle for tennis engagement as the U.S. Until the emergence of stars like Raonic, Eugenie Bouchard and Vasek Pospisil came onto the international scene, Canadians took relatively little interest in the sport. But Raonic's story as a little boy with a powerful vision has captured the nation and their attention.

Raonic is just one athlete whose story can be unpacked through the movement of the body. Other dancers we interviewed saw the similar themes in the movements of the tennis players, particularly in relation to non-traditional dances like contemporary, modern, musical theater and hip-hop. The result is more than just a reinvention of postures, positions, and steps with a new vigor and captivating elegance, it’s an insight into how the game can be retold in a new and interesting way through each athlete’s performance.

“They are thinking on their feet and reacting with their whole body as a response to the stimulus of the ball, not knowing what could possibly come next.” Alex Klarer (the dancer featured in Part I) says. Her insight displaces the centuries old stereotype of the calm, strategic player and instead, embraces a new take on the player’s mindset – one where apprehensions and anxiety might play just as much into his game as power and technique.

Kyla Berry – a Long Island native with over 13 years of experience in hip-hop, reggae, and jazz – noted how just like dance, tennis also tells a story of constant energy and focus.

“If, as a hip-hop/reggae dancer, you didn’t move with certain speed to produce the choreography, that particular movement would not come out looking the way it should….with tennis players, their movements require similar configurations: moving with vigorous and hastened speed to hit the ball (and score).”

As tennis searches for a new way to tell the story of an old, reserved game to a larger audience, we can’t help but turn to the movement of the body, in motion, as a means to an answer. The body serves as medium through which storytelling is conveyed across disciplines and conveys the expression of our deepest selves and of the human themes that surround our everyday lives. It’s through the retelling of the body’s story, that tennis may find its answer as a sport. After all, at its core, the separation of athletics and artistry is only divided by what means to an end the body conveys. We will wait to see if the world of tennis joins the dance.