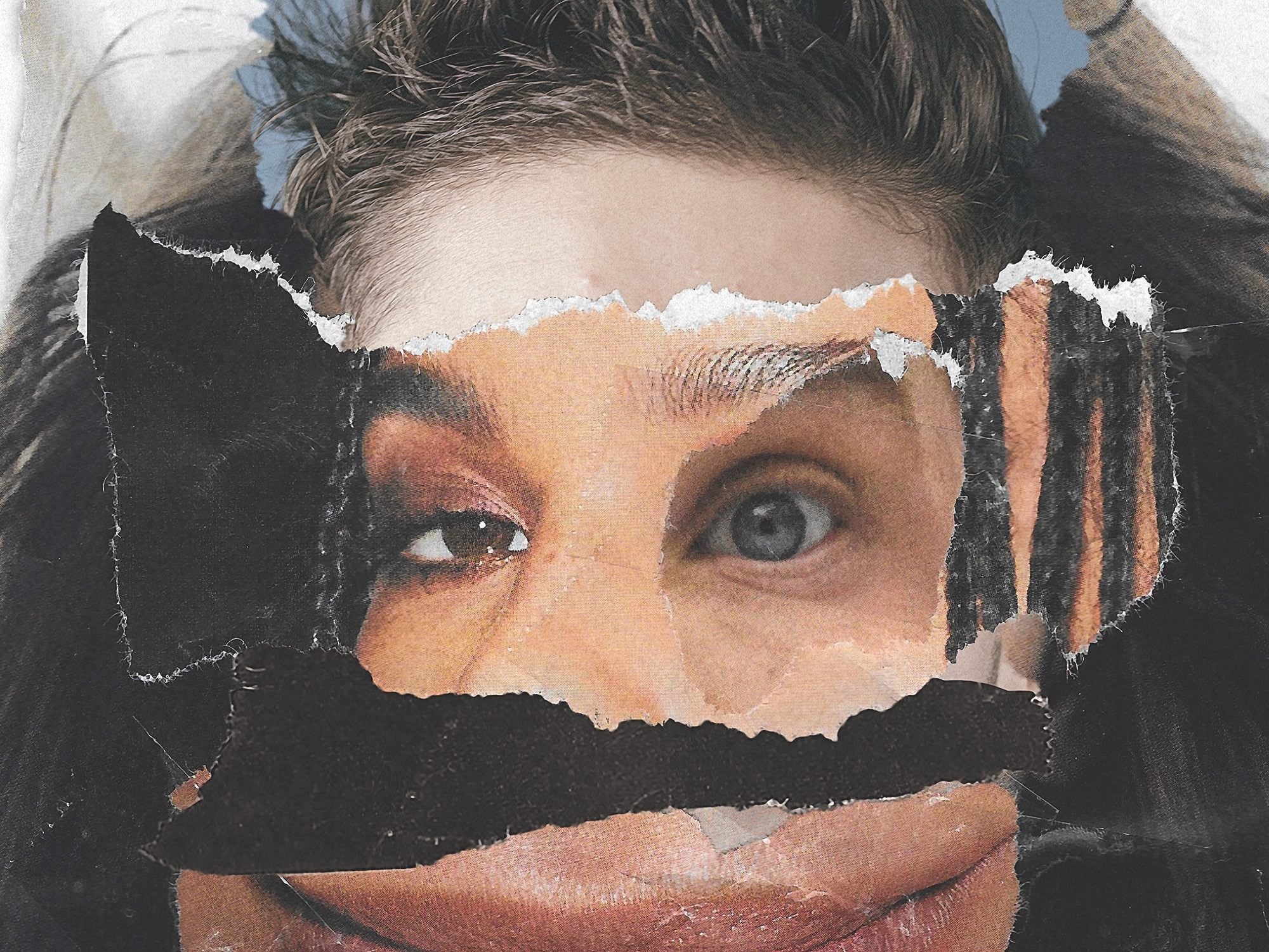

The perspectives of racial issues told by individuals from our community.

Introduction by Justin Chan

America is built on race. Our country’s history, filled with periods of light and darkness, is a testament to that fact. From the century-old horrors of slavery to the election of the first African American president, this nation has experienced its fair share of highs and lows. As its racial makeup continues to increasingly diversify, groups frequently ignored in a seemingly black-and-white public sphere have made their voices known. Still, the conversation on race, as a whole, has often been reduced to an overly simplistic discussion of one’s race in the context of whiteness, when, in fact, whiteness is but one of many factors that shape our perceptions of ourselves and each other.

Perhaps no one has sparked a fiercer debate on race more than Donald Trump, a president who has marginalized the disenfranchised with a series of controversial statements, cabinet appointments, and executive actions. In the spirit of nationalism, Trump has started a movement that threatens the very rights of those whom his predecessor Barack Obama fought to protect: African Ameri-cans, Hispanics, Asian Americans, and Native Americans. At a time when the voice of this country’s minorities is more important than ever, UNDO-Ordinary asked people of all backgrounds—white included—to address some of the most pressing racial issues they face.

The Asian Voice

Jaeki Cho

I remember watching Rush Hour and Lucy Liu on Ally McBeal. As a 9-year old, newly arrived immigrant in America from China by way of Korea, I had no context about life as an Asian American. I didn’t question Chris Tucker’s blatant racist humor nor did I wonder what was wrong with Ling Woo’s Dragon Lady stereotype. Frankly, I was ignorant. After all, America wasn’t yet MY country. It didn’t help that the parts of Queens, New York where I grew up had few people that resembled anyone on T.V. I lived in a bubble, an isolated community of yellow, brown, and Eastern European immigrants that preferred languages other than English.

Then I acquired my green card and became eligible to obtain an American citizenship. That’s when it hit me: “My ethnicity is Korean, but I’m an American.” The newfound realization made me reflect on experiences that I should’ve met with resistance rather than compliance, from being called a “chink” by a Black father and son in Queens Center Mall to helplessly listening to my science teacher telling me to “go back to my country” because I disagreed with President George W. Bush’s foreign policy.

Up to that point, America as a country had felt distant and foreign. Now, it was home–or at least, ostensibly my home. I knew this home shouldn’t be a place where my identity should get painted with a single brushstroke, which often happened without my consent. As a taxpaying, law-abiding member of the American society, I now feel a responsibility to correct anyone who attempts to portray me–or anyone resembling me–in a fashion I deem inaccurate.

I was most recently troubled to hear Reggie Ossé, host of the podcast The Combat Jack Show, repeatedly mention that “Asians are the new Whites.” It also bothered me to watch a lone Japanese character stand alongside a group of villainous, rich, white liberals in Jordan Peele’s film Get Out. Both are examples of insensitivity and display one minority’s general lack of care for nuance in its attempt to characterize another. To be fair, some of these assertions or characterizations aren’t completely baseless. Due to cultural and language gaps, many first-generation Asian immigrants are either ignorant or indifferent to issues of race. Plus, the model-minority label birthed in the ’60s by White journalists continues to persist and is even embraced by conservative Asians. But it’s misleading to typecast the entire Asian race as no different than the White majority, especially considering the sparse representation of Asians in any form of mainstream media. How can Asians, the most underrepresented minority group, share the same benefits and privileges of the white majority?

There are 4.5 billion Asians in the world. About 18 million reside in the United States of America. That’s only 5.6 percent of the entire U.S. population, yet it’s still a number that’s significant enough for many to realize that the foods we Asian Americans eat, the languages we speak, and the lives we live are vastly different from each others. Our economic, educational, and political affiliations also vary, just like those of White and Black people.

To shatter this misconception that Asians are the “new Whites,” Asian creatives need to spearhead more engaging content in the fields of music, literature, art, and film. Hip-hop introduced me to parts of American history that were omitted from school textbooks. It shed light on race relations better than any platform. To improve understanding of Asian Americans amongst people of color, representation in media needs to improve. Only then can Asian Americans be accepted as their own unique group—not “new Whites” or model minorities, but just Americans.

Rula Al-Nasrawi

Dear America, We gave you our tired and our poor. My grandparents tried to find a home in you. Being an immigrant is like replanting a fully grown tree in new soil and expecting it to survive. My jidoo was a redwood tree. He grew up in Baghdad and moved to England to attend the London School of Economics. He had green eyes and Anglo features. My bibi was different; she hardly spoke English, had poofy hair, and a hooked nose. Jidoo met her when he was back from university. They moved from Baghdad to England to the United States.

My jidoo warned my mother against naming her son Hussein, arguing that naming a child after an Arab dictator would bring nothing but trouble. She named him Hussein anyway. Because in Arabic, Hussein translates to “good looking.” Because she loved King Hussein of Jordan. Because she wasn’t going to let new soil decay old roots.

My jidoo died when I was 8 years old. He had a brain hemorrhage while watching Jeopardy, his favorite American show. My bibi died of a broken heart and cancer a few years later. Their home in Baghdad stayed intact through the Gulf War, the Iran-Iraq War, and the Iraq War. I’d like to think they’re back there now.

So what of my people? What of the Sunni, the Shia, and the Kurds? Babylon? What of the Tigris? What of the goddess Ishtar spreading her bloodstained wings?

Dear America. Have you come to teach us about consumerism and corn syrup? Student loan debt and mass layoffs? Startup culture? Starting over culture? America, you are broken. Not me. Not my mother, or father, or grandfather, who came here to flee hatred and bloodshed only to find hatred and bloodshed proudly donning a blonde toupée.

My jidoo was Iraqi but part of him wanted to leave that behind. Because brownness complicates things. He passed this sentiment onto his children, and they passed it on to us. “You don’t need to say you’re Muslim,” my mom said. But I lived in a Muslim household. My mother threw her slippers at me when I gave her attitude. There is always hummus in the fridge. My mom prayed when her parents died. My family thought that feigning Whiteness was the answer, but I knew the brownness was unshakeable, and I needed it that way.

Dear America, I am the daughter of Shia Muslims from Baghdad. I drink tequila, I swear, and I love bacon. Airports will give me anxiety forever. My brother shares a name with someone on the no-fly list. My father lost customers at his business when people learned he was a Muslim. I don’t pray, but if I did, I would pray for enough money to buy land for my parents and re-grant them the American Dream they want so much for me. Until then, I want my tired and my poor back. I have no more left to give.

Seher Sikander

It is now my third time writing this from scratch. I wanted to talk about my childhood, trauma, being an American-born Pakistani, straddling a myriad of identities and not fully belonging anywhere, hate crimes, 9/11, model minorities, and entertainment—it was a list that continued to grow longer and more complex the more I wrote. Before any real conversation can even begin, I need to be recognized and considered. In a country of racial binary, that space for me does not exist.

What hurts most is when I find even my most intelligent and good-hearted peers seemingly trapped in a dangerous myopia when it comes to conversations on race. Time and time again, I’ll try to pull them out of the binary and say something like, “Let’s explore what this means when we also consider everyone else that isn’t Black or White.” They’ll offhandedly say, “Oh yeah,” and follow the prompt for a second, only to reflexively revert to their old thought process. It’s alarming and painful to witness.

Sometimes, when people catch themselves in this simplified dichotomy (I see this happen in the media and public spaces all the time), the term “Latino” is used loosely to account for brown folk. It feels careless, disingenuous, and incomplete. “Diversity” and “inclusion,” to most White people, means ticking off a box. When you don’t consider diversity as a sum of its many unique parts, the inevitable result of that thinking is hollow and incomplete.

Operating in a state of black-or-white polarity is a convenient way for many to compartmentalize and digest the topic of race, but it’s the grey area that’s difficult, uncomfortable, and closer to the reality of the world we live in. Coming up with a solution that addresses oppression at its root requires that we recognize all of the complicated shades of experience and identity that fall along the vibrant spectrum between Black and White. To this point, one thing I often hear is that South Asians are racist and don’t welcome Black people the same way Black people welcome everyone else. It is a valid point that I hear a lot because I have seen this sort of discrimination and experienced it myself.

I am as uncomfortable, if not more so, in a room of South Asian people as I am in a room of all White People. I’ve spent my life feeling like an outsider in most places, especially in the Pakistani American community where I grew up and in Pakistan itself. The insular nature of the South Asian community has led to a xenophobia that has affected even its own people. I believe it’s important to change the closed-mindedness that holds South Asians themselves hostage.

Pakistani Americans exist, and I ask that you find the space to see me. America is not black and white—it is black, white, brown, and everything in between. Self-identification is one thing, but in a nation where we simply become whatever arbitrary thing we are assigned by false leaders, we as a people all need to come together to get through these dark times.

The Hispanic Voice

Marisol Martinez

Why do you sound like a White girl?

Excuse me, what do you mean?

I mean you sound White!

What does sounding “White” mean?

You know, you don’t have an accent and you don’t sound like you’re from the hood.

Um, that’s because I didn’t grow up in the hood.

I have spent the last decade of my life having this conversation with people from all walks of life. It always baffles me when people think or say such a thing, but, even more so, it makes me intensely sad. It upsets me because these people have an expectation of me from their limited understanding of what they think a “Spanish” girl should be. I’ve hated having to explain my upbringing and “why I sound like a White girl.”

What does it even mean to “sound White?” It’s something that haunts me. I grew up in the suburbs and the city, not in a housing project or “the hood.” I was blessed to have parents who worked their asses off to build a successful business, which gave me the opportunity to attend great schools. At the time, those great schools were mostly Caucasian. Today, they’re not the same—they’re much more culturally diverse than when I attended them. That being said, I spent most of my grammar and high school years around a lot of White people. At home, though, my mother spoke with an accent, and I had grandparents who spoke very little English. That was my upbringing: a little bit of this, and a little bit of that. It was a mix of two worlds, at best. I don’t think the way I speak makes me sound like a White girl. I think it makes me sound educated.

Here is what I want you to know about being a Colombian-American who was born in America and raised in the suburbs and the city. We are not all from the hood, our parents are not drug dealers or emerald smugglers, we are not part of the cartel, and I have no connection to Pablo Escobar. I’ve never tried cocaine in my life, let alone any drug. We are not all poor, uneducated, and on welfare. We are smart, educated, hard-working, family-oriented, and God-loving people. I’m sick of people stereotyping any race, especially in a country that is so racially diverse and mixed. Who the hell are we to have judgment towards anyone’s upbringing and race? Why can’t we just look at each person as an individual instead of marginalizing him or her into a group? Are we creating separatism instead of inclusion by doing this? My hope is that instead of looking at race and diversity as a bad thing that causes evil in America, we can actually turn the Trump era into a positive thing and celebrate each other’s contributions that are making America great again.