Not everything is black and white. Too often, our conversations neglect those of mixed races.

Introduction by Justin Chan

Each person can have a different number. One, two, even as many as three. It's rare that the conversation ever gets to the fourth guess though. Having multiple racial identities isn't uncommon anymore—in 2013, for example, nine million Americans chose two or more racial categories when asked by the U.S. Census Bureau about their background. Although the Pew Research Center reports that there is now 10 times the number of multiracial babies than there were 40 years ago, men and women of mixed race usually walk around with an alien-like mask. People compute outrageous baseline opinions about each other within seconds of meeting, but multiracials skew the math.

In an era where racial identities are often discussed without a care for nuances and grey areas, people of mixed race see opportunity and a chance to expand not only our own but others' perceptions of color, beauty, and body. Studies show that multiracial people are more likely to be welcoming of different heritages, and almost 20 percent say it's been some kind of advantage in their lives.

Our era of identity politics has sparked a new kind of conversation. Ethnic identity is either celebrated or seen as a hindrance to "progress." In reality, we're all just getting to finally know each other. Multiracials continue to transcend our definition of what race is and serve as the bridge to a new social compact where the world must include them in conversations that have long been rooted in single-race, monocultural institutions. They're spearheading the future. As our impression of race continues to evolve, UNDO asks several multiracial individuals to discuss where they fit in today's society.

Dani Concepcion - Filipino and Honduran

To me, being biracial is an honor. And I don't mean that as being better than anyone else. I simply think that having the spectrum of two different cultures is lucky. The opportunity to be educated in two ethnicities—I mean, who wouldn't benefit from that? So, growing up biracial was never a battle for me. I always knew that I was special. And "special" meant I didn't need to feel like I was one thing or the other. My parents never forced me to have to be from the Philippines or from Honduras. My parents came to New York to make a life. I think that's what made the biggest impact on my upbringing. Being born in the Bronx, I knew that I was and always will be American. The kids I grew up with never brought attention to how different we were from each other. For the most part, the only thing we really worried about was who had a crush on whom.

The past election has only made me more curious about the societal makeup of America. I've always been a little ignorant to racism because of how much my family and I have felt welcomed here. I'm sure we've had bits of racism here and there from strangers, but my parents always prevailed. Looking back at those moments, I feel they did an amazing job raising me to become a strong-minded individual. 2017 is the perfect time to remain positive. I have a 2-year old and all I see are endless possibilities for her to help the nation. I believe that bringing her up the way I was brought up will help us move forward. She will be a beacon of light when the time comes. I think our future generation needs to be heard. I think of myself as my daughter's megaphone. We made Barack happen, why not hope for our children to make something good happen in their future?

My fight right now is creating that foundation for my daughter. My fight is not allowing an individual to plant seeds of hate early in her life. Her dad is Creole, so she's also biracial. As her parents, we have to be proactive in highlighting how special she is. She will inevitably experience what I have gone through all my life. Unfortunately, she will have two things that she will be judged on at first sight: her looks and her gender. I fight every day by working hard to excel in life, not because of my race or gender, but with the quality of my actions. I fight so that she won't just be a "biracial female" notch on life's belt. I know she will succeed because I fought the good fight for her. This starts with me being an example for her.

It's never too late to learn to love. Seeing the good and the bad is one thing, but my job is to educate her in understanding the difference between good and bad. I see the anger in everyone these days. Call me naïve, but that energy just drains me. Last time I got upset, I literally passed out at 8 P.M. and didn't wake up until the next morning. It exhausted me. When I walk down the street, my objective is not just to get from point A to point B. My objective is to affect someone's life positively on my way to point B by sharing positive vibes through a smile, a greeting, or a nod. Simple acknowledgment goes a long way. I know anytime I get a positive greeting from someone, it always sets the tone. I share the vibe.

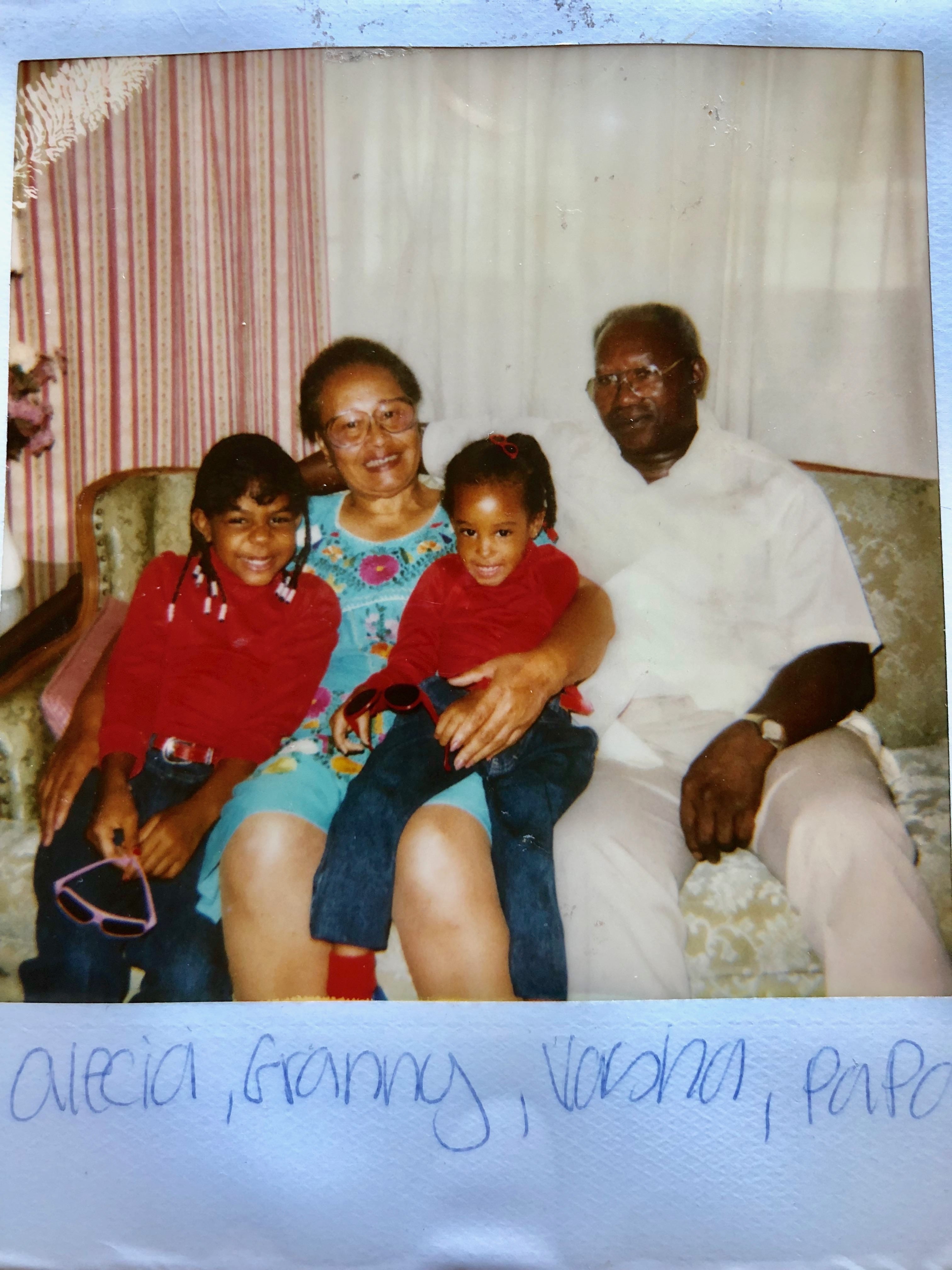

Jesslyn Reyes - Chinese and Puerto Rican

What are you? I love when people ask me that. I sometimes tell them I am a unicorn, or better yet, that I am clearly an alien sent from outer space set out to destroy anyone who cannot see that I am not a "what." If you must know, my ethnic background is Chinese and Puerto Rican. Throughout my whole life, people around me have made their own conclusions about what ethnicity I am. "Oh, you're not Puerto Rican, you're just Chinese." Or "You're not considered a minority, your skin is white," and my favorite, "So, you're basically just Filipino." What I really am is a New Yorker.

I grew up in a Hispanic neighborhood—I speak Spanish and can relate to every other Hispanic in New York City. I also celebrate Chinese New Year and have dim sum, although I cannot really say that I am in any way in touch with my Chinese roots. It was hard growing up in a predominantly Hispanic neighborhood and not looking like everyone else. In kindergarten, we had to create little paper beings with our flags of origin, and my paper being was the only one with two flags. I've had Chinese food thrown in my hair, Asian slurs yelled at me, and people talking about me—sometimes with my mother—in Spanish right in front of me. I never wanted to associate with my Chinese side because I was surrounded by hate in my community. My mother felt the same way and never really taught me anything about her culture. Even though we would eat Chinese food and my aunt would give me little red envelopes on Chinese New Year, my real education on Chinese culture was through my Chinese friends.

My parents taught me and my brother good morals. If I came home from my first grade class saying, "I don't like Italians," because some Italian boys were making fun of me that day, they always made it a point to let me know that it was wrong of me to think like that and to respect everyone regardless of what they look like. That was and still is one of the biggest life lessons I have ever learned from being multi-ethnic. I've always wanted to be treated with respect even though I was not always given that. I lead by example and accept everyone regardless of who they are because everyone deserves that opportunity.

Unfortunately, not everyone in America sees it that way—especially now with Trump in office. I cried when he was elected. I cried as a woman, as a minority, as a Hispanic, and as an artist because I do not feel welcomed in "his" America. He defies everything that I was ever taught to believe in, and I don't want children of any ethnicity to grow up with that hate in their minds because I know they can be the change that this country needs to actually make itself great again.

Jessica Morgan - Israeli-German and French-West Indian

I always feel quite lucky being biracial. As an adult, I am always referred to as the one who is "the best of both worlds," but it hasn't always been that way.

"What are you?" is a question I get asked on a daily basis, and, often, I chuckle thinking they are joking, but, judging by the vacant look in their eyes, I realize what they actually mean is, "Where are you from?" When I tell them that my mother is Israeli-German, my father is French-West Indian, and both sides of my family have African roots, the answer stops them in their tracks, and, suddenly, they are surprised. Race is not clearly defined. Being biracial paints a blurred line that is both fascinating and illuminating, but people seem to think race is polarized.

My biological parents were, unfortunately, unable to look after me, so I was put in the English care system. At the start, I moved in with five different families in London. I was a rather naughty child and slightly misunderstood; I hated White and Black people. I didn't understand where I came from, and I didn't know where I was going. At 5 years old, I was finally adopted by my foster carer's daughter, who was born in Grenada, the "Spice Isle" of the Caribbean, and her husband, a British-born Jamaican. It was through them that I was able to enjoy soul food, cussing, and family traditions.

When I was 12, we were uprooted to the east coast of England to a fishing town called Leigh-on-Sea, which was far from the diversity I had seen in London. I was the only biracial girl in my school, an all-girls private institution. Being mixed race in the 90's meant I didn't have much to identify with other than my mother, Scary Spice, and Tracy Beaker, a fictional TV show about a young British girl who lived in a care home. Moving to the suburbs, I felt like the odd one out. People would stop me in the middle of the street just to touch my hair and then proceed to tell me how beautiful it would be if I straightened it. People would stop my mum to ask if my dad was Black or White and how she "made" this "exotic-looking" girl.

Teachers, friends, and boyfriends would continuously encourage me to straighten or dye my hair because that was what was considered beautiful. The pressure subsequently made me hate the way I looked. I hated being biracial. I never fit in anywhere. When I did identify myself as being black, I was told I was not "really" black and that I was "light-skinned."

Growing up without an identity and lots of uncertainty put a strain on my mental health. My hair went from blonde to red to blue to straight to curly to almost falling out. I was eventually left with burnt ends and an uneven hairline as a result of the constant use of chemicals and hot irons. My self-esteem was broken, and I lost my identity.

One weekend when I was a teenager, my mother decided to take me to a hairdresser to fix my hair. To our horror, we were turned away from the stylist who claimed he "didn't do black hair." Though he wasn't explicitly racist, turning us away because of the texture of our hair was hurtful. We eventually styled and cut my hair at home.

Despite living in a predominantly White area, I was subjected to casual racism from time to time from both races. I was too White for the Black kids and too black for the White kids. That meant being called "half-caste" or "half-breed." I eventually learned to ignore the critics and begin to love myself. I started researching biracial celebrities, writers, actresses, and I printed their pictures for my wall. I admired their beautiful features and big-and-full-of-life hair and yearned for mine to be the same. Alicia Keys, Beyoncé, Thandie Newton, Mariah Carey, Halle Berry—the list went on. I spent hours and hours on YouTube, watching curly hair routines in a bid to learn about the texture of my hair and how to look after it properly. Today, I'm at a place where I fully appreciate my mixed heritage.

With every passing day, I've grown my hair out and learned to love myself just the way I am. I've embraced my culture and heritage and accepted that I am fortunate to have a foot on both sides of the fence. Being of mixed race is a gift. Even though I may be racially ambiguous to some, instead of introducing myself as what I am, I introduce myself as who I am: a journalist, a runner, a singer, and a woman with dreams, hopes, and aspirations.

As a mixed-race woman, I've watched in horror as both sides of my background I define as my own have become victims of the media, which has perpetuated stereotypes and reminded us that the world has perhaps only placed Band-Aids over the problems that have never been healed at their very core. By understanding our roots clearly, we should be proud of our complex family tree—those roots are part of our genetic makeup. We should embrace race, culture, and heritage by researching and educating ourselves.

I couldn't be prouder of where I come from. Two halves make a beautiful whole, and now, more than ever, I feel complete.

Jason Duaine Hahn - Mexican and Caucasian

When I was a child, I noticed early on that my skin wasn't as tan as my father's nor was it as white as my mother's. I'd look in the mirror to study my face and body, and I couldn't pinpoint a single feature—a nose, a chin, an eyeball—that seemingly came from my White mother or my Mexican father. For a while, I legitimately wondered if I had been switched at birth.

Back then, I hadn't entirely grasped the concept of race, let alone what it meant to be biracial. I had only seen my father sporadically throughout the years until he gained custody of me from my maternal grandmother when I was nine. A combination of being forced from the only home I had known to live with a father I hardly knew—and eventually being subjected to his alcoholism and abuse—led me to reject my father and the Mexican culture that was so important to him. I refused to say the Spanish words he taught me, I vomited the Mexican food he fed me, and on the standardized tests at school, I'd check "White" when they asked for my race.

As the years went by, the reactions I received from others eventually led me to accept and identify with being Hispanic. Even though I couldn't look in the mirror and recognize who or what I looked like, people decided for themselves. I'd have a Hispanic person ask me for help in Spanish and have to look into their trusting eyes and say, "No hablo espanol." I'd hold a door open for a White person and get a "Gracias" in reply or park in a valet area and get asked by someone looking for his or her car, "Can I get my keys?"

I began to feel the absence of the culture that so many people associated with my appearance. I took college classes that focused on Latino and cultural literature. I started to reconcile with my father enough to finally immerse myself in the culture I had missed. By then, he was deported to Mexico.

I will never fit perfectly into either being White or Hispanic. I will always be both, and learning about the significance of being Hispanic in America will be a lifelong journey. Now that I'm older, my father's physical features in me have become more apparent. I don't entirely see him, though. Instead, I see a clearer version of myself.